A Study Sneak Peak: Risk of Low Energy Availability, Disordered Eating, Exercise Dependence, and Fueling Habits in Trail Runners

As an ultrarunner for over a decade, I have witnessed first-hand the slow shift in the narrative around fueling. As a young runner, I never talked about fueling, rarely fueled for long runs, and fueled poorly during races. I also didn’t hear my running buddies talk about fueling, so I didn’t prioritize it. As I continued to grow and learn, I realized that fueling was extremely important for success and to my overall health and the narrative in the sport evolved with me. After years of suffering from low energy availability (LEA), I slowly accepted help and started prioritizing fueling and recovery. I started talking about the importance of fueling and watched my community also start to prioritize fueling around me. Despite this slow shift, countless athletes still inadequately fuel for their runs and races, whether on purpose or accidentally, and I wanted to understand why. To get a better sense of how common this is in the broader trail and ultrarunning community I knew we needed to ask some bigger questions. The answers we got will hopefully highlight some of these issues and finally change them.

Mirroring my experience as an ultrarunner, other scientific studies have also highlighted the prevalence of these disorders in our community. These limited previous studies indicate that trail and ultrarunners may have a high prevalence of disorders like low energy availability, disordered eating, and exercise dependence and that we [ultrarunners] typically do not meet fueling recommendations during ultramarathon events (4,5,12,13). When we don’t fuel properly for our endurance events, we put ourselves at higher risk of not meeting our energy demands for the day, which can eventually lead to low energy availability. We have also found that things like disordered eating, body image issues, and excessive exercise may contribute to inadequate caloric intake.

Due to the lack of studies in this area, one year ago, Dr. Kelly Pritchett and I set out to survey many ultra and trail runners about disordered eating, symptoms of low energy availability, and fueling habits, and over 3,000 of you took the survey! Our study had a couple of purposes:

- Our first aim was to figure out how prevalent low energy availability was in our population of trail and ultrarunners.

- Our second aim was to get a good sense of how the average trail or ultrarunner fuels during training runs and races and if improper fueling during exercise is related to the runner’s risk of low energy availability.

- Finally, we wanted to learn about the prevalence of disordered eating and exercise dependence in this population and how they are related to both low energy availability and fueling habits.

Our study is scheduled to be printed in the International Journal of Exercise Science this Fall (7). Many of you participated in it, and we thank you so much!

Before I dive into the nitty-gritty of the study, like ultrarunning science also loves acronyms – so let’s define some of them for you.

Low Energy Availability (LEA): LEA can be thought of as what occurs when we don’t consume enough energy to account for how much energy we burn going about our daily lives, whether it be digesting our food, or running a marathon (9; 10). LEA can occur both intentionally (restrictive) or unintentionally. LEA has been shown to impact a lot of our bodily processes, like our hormones and metabolism, which can result in many negative health outcomes (1). In this study, we measured risk for LEA by the LEAF-Q, a questionnaire validated in female athletes aged 18-40 that looks at things like, menstrual function, past injuries, and GI function (aka poop!). (11).

Disordered Eating (DE): DE can range from unhealthy dietary habits such as skipping meals, calorie restriction, and excessive exercise to lose weight, to less severe characteristics observed with eating disorders (3, 14). We measured this risk level in our population by administering the DESA-6, which is a validated questionnaire categorizing participants as either “at-risk” or “not-at-risk” based on specific questions around body image, weight, and fueling habits (8).

Exercise Dependence (EXD): EXD describes an unhealthy preoccupation with or addiction to exercise, sometimes prioritizing exercise over your own health, loved ones, or work (6). I’m sure you’re all rolling your eyes at this one, thinking, “We’re ultrarunners, of course, we are addicted to exercise.” And based on the findings of our study, you’re spot on, but is that something we should strive for? We measured this with the Exercise Dependence Scale, which asks athletes a series of questions related to their exercise habits, how they feel when they cannot exercise, and what they are willing to sacrifice for exercise (2,6).

The Study:

We designed a 45-question survey that included training and racing characteristics, questions regarding carbohydrate intake and questionnaires specific to LEA, DE, and EXD. See Figure 1 below for the specific questionnaires, classifications, and fueling questions.

Population of Runners:

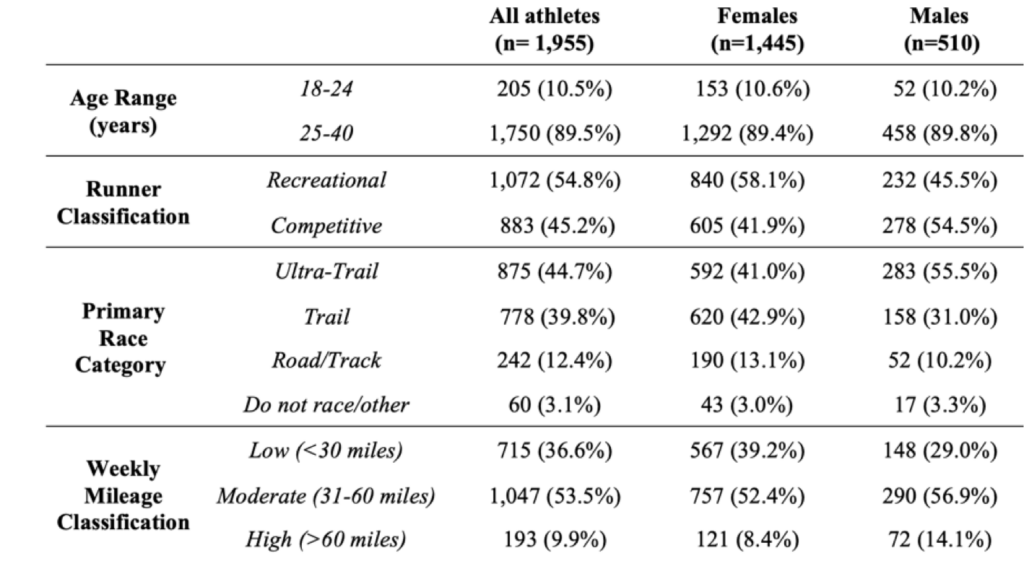

We had a phenomenal turnout of survey responses, topping out over 3,000 participants. However, for our first paper, we focused only on runners between the age of 18-40 (n=1,955; males: n= 510, females: n=1,445). All participants self-identified as a “trail or ultra-runner” and were between the ages of 18-40. The majority primarily participated in ultra-trail races (> 50km in length) or trail races (<50km in length) and ran 60 or fewer miles per week. Aka, most participants did exactly what most of us do.

The Findings:

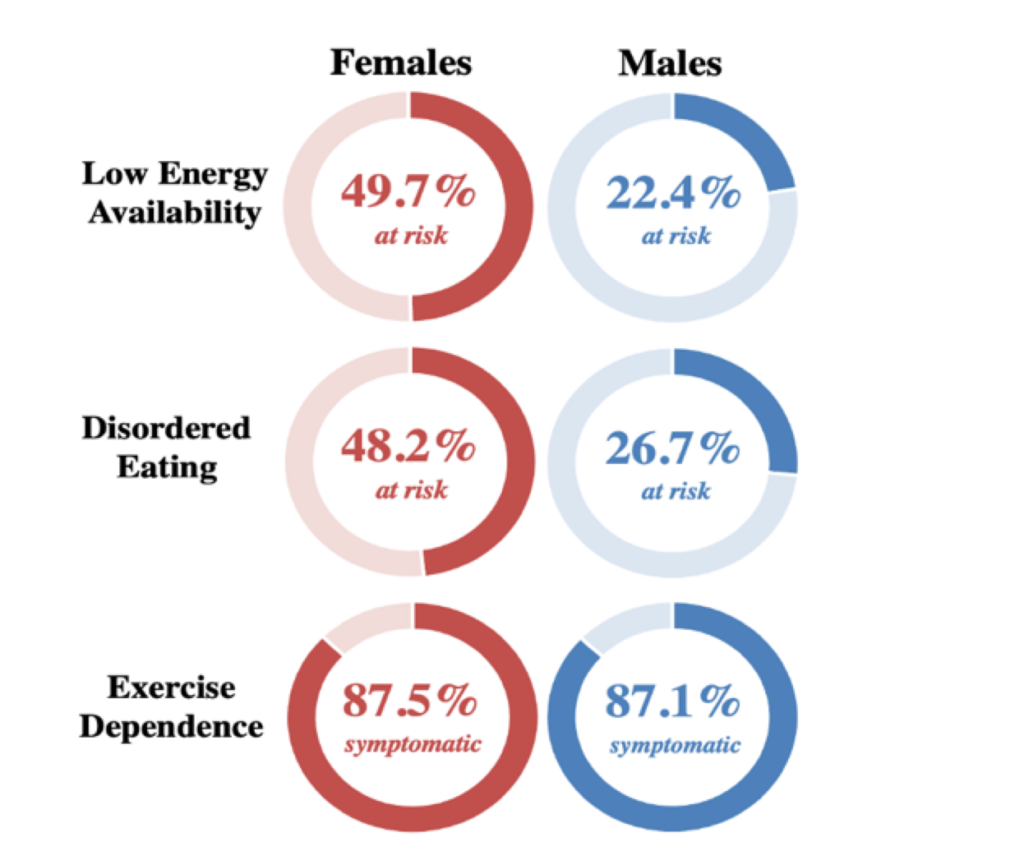

Low Energy Availability

Slightly less than half of all trail runners experienced LEA, with females two times the risk of males. Disordered eating risk followed a similar rate in females and males. However, when it came to exercise dependence, shockingly, 90% of athletes were symptomatic (is it really that shocking?)

Athletes at risk for LEA were more likely to also be at risk for DE and EXD. This means that there may be a relationship between disordered eating, exercise dependence, and risk for low energy availability. This makes sense, as deliberately restricting calories or exercising excessively could lead to symptoms of low energy availability, since caloric demands may not be getting met. This is something to consider when working with athletes, or thinking about your own relationship with exercise and fueling, really emphasizing the development of a trusting relationship to better understand fueling habits and motivations behind training.

Fueling – Finally!

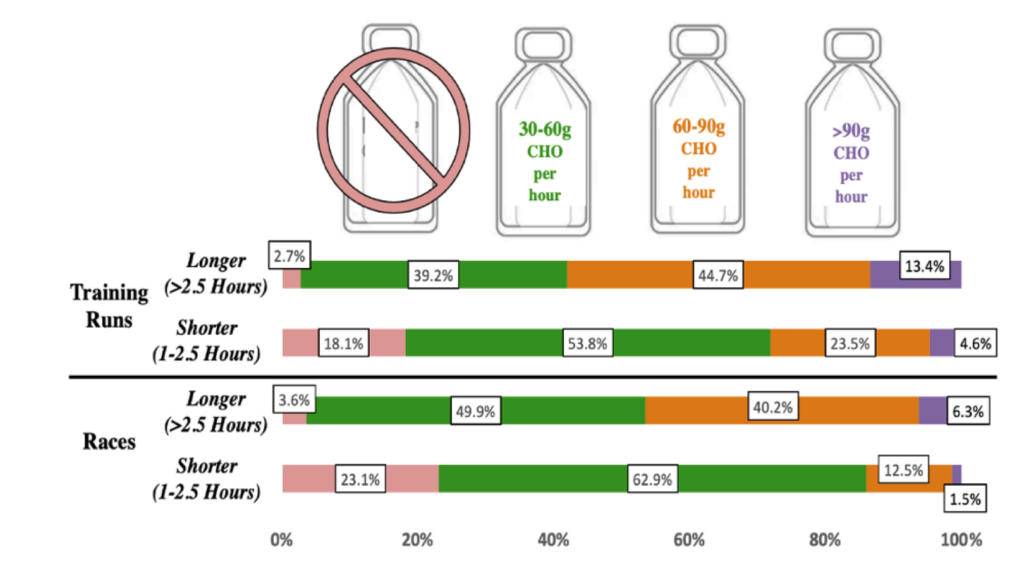

In general, most athletes are fueled well enough for runs less than 2.5 hours long. However, a large percentage of trail runners failed to increase their consumption of carbohydrates for runs lasting longer than 2.5 hours. We also found that female runners who did not adequately fuel for runs were more likely to be at risk for LEA.

Like most studies, there are limits to how we can interpret the findings and the population of trail runners willing to take our survey may also have impacted the results. We admit that these ranges of carbohydrates may not be necessary or attainable for everyone and that we need more information on how fueling needs may vary for everyone. However, this initial glimpse into the fueling practices of ultra and trail runners has helped fuel our hypotheses for future studies and serves as a good reminder to the community about the importance of fueling and the prioritization of mental health when participating in this sport we love. Dr. Pritchett has provided her interpretation and recommendations regarding our findings below.

Interpreting and Applying the Results with Dr. Kelly Pritchett:

- Given that the risk for LEA was high in this group of runners and the relationship between risk of LEA and inadequate fueling habits during training and competition lasting > than 1 hour indicates the importance of meeting carbohydrate intake recommendations during exercise to avoid negative health outcomes.

- Athletes should aim to consume over 30 grams (the equivalent of ~1.5 Gu energy gels) of carbohydrates per hour for endurance activities between 1-2.5 hours and over 60 grams (the equivalent of 3 or more Gu energy gels) of carbohydrates per hour for endurance activity over 2.5 hours.

- If you aren’t used to fueling, start small. Taking small bites of a gel over 10-15 minutes may make it go down easier and allows you to build up your tolerance to more calories. Sip-sip, nibble-nibble. Slowly increase the amount you are eating during your runs until you get into a range that works for you!

- During times of increased training, athletes need to eat more to support their metabolic and endocrine systems, to adapt to the training stimulus, and to optimize performance. This may require additional work to ingest adequate energy around and during training, especially when appetite does not match the energy needed.

- Consume a post-exercise snack that is high in carbs in addition to protein.

- Increase the amount of carbs in your pre-exercise snack (think of things like an extra scoop of oats, bananas, or sweet potatoes).

- Symptoms of EXD and DE may be red flags for identifying risk of LEA in trail runners.

- Restoring the energy deficit is necessary for optimal energy availability and for reducing the negative outcomes associated with intentional or unintentional LEA.

- Athletes should be referred to a registered sports dietitian for assessment and treatment of LEA as a reduction in exercise energy expenditure, and an increase in energy intake are necessary for correction of LEA.

- In the case of intentional LEA, the athlete needs a higher level of care. A collaborative team approach that includes a sports medicine doctor, and a psychologist with expertise in eating disorders/disordered eating (ED/DE) in athletes must be a part of the treatment team if ED/DE is present.

I challenge each one of you to add an extra boost (gel, gummies, liquid calories, cookie, <<whatever makes you excited to eat goes here>>) to your next run, and to hold your training buddies accountable when it comes to fueling during and after your epic adventures this summer.

References

(1) Areta JL, Taylor HL, Koehler K. Low energy availability: history, definition and evidence of its endocrine, metabolic and physiological effects in prospective studies in females and males. Eur J Appl Physiol 121(1):1-21, 2021.

(2) Bamber DJ, Cockerill IM, Carroll D. The pathological status of exercise dependence. Br J Sports Med 34(2):125-132, 2000

(3) Berg S, Pritchett K, Ogan D, Larson A. Self Reported History of Eating Disorders, Training, Weight Control Methods, and Body Satisfaction in Elite Female Runners Competing at the 2020 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials. Int J Exerc Sci 15(2):721-732, 2022

(4) Costa R, Swancott A, Gill S, Hankey J, Scheer V, Murray A, Thake C. Compromised energy and nutritional intake of ultra-endurance runners during a multi-stage ultra-marathon conducted in a hot ambient environment. International Journal of Sports Science, 2013.

(5) Folscher L, et al. Ultra-Marathon Athletes at Risk for the Female Athlete Triad. Sports Med Open 1(1):29, 2015.

(6) Hausenblas HA, Danielle SD. Exercise Dependence: A Systematic Review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 89–123, 2002.

(7) Henninger, K., et al. Low Energy Availability, Disordered Eating, Exercise Dependence and Fueling Strategies in Trail Runners. International Journal of Sports Medicine. Pre-Release. 2023.

(8) Kennedy SF, Kovan J, Werner E, Mancine R, Gusfa D, Kleiman H. Initial validation of a screening tool for disordered eating in adolescent athletes. Journal of Eating Disorders 9(1), 2021.

(9) Logue DM, Madigan SM, Melin A, et al. Low Energy Availability in Athletes 2020: An Updated Narrative Review of Prevalence, Risk, Within-Day Energy Balance, Knowledge, and Impact on Sports Performance. Nutrients 12(3):835, 2020.

(10) Loucks, AB. Low energy availability in the marathon and other endurance sports. Sports Med. 37:348–352, 2007.

(11) Melin A, Tornberg AB, Skouby S, et al. The LEAF questionnaire: a screening tool for the identification of female 1athletes at risk for the female athlete triad. Br J Sports Med 48(7):540-545, 2014.

(12) Stellingwerff T. Competition Nutrition Practices of Elite Ultramarathon Runners. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 93–99, 2016.

(13) Stellingwerff T. Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Shared Pathways, Symptoms and Complexities. Sports Medicine 51(11):2251-2280, 2021.

(14) Wells KR, Jeacocke NA, Appaneal R, et al. The Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) and National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC) position statement on disordered eating in high performance sport. Br J Sports Med 54(21):1247-1258, 2020.