A note from Freetrail: The second in a recurring Coaches’ Corner collection with Ruby Wyles. This month’s article is part two of a two-part series all about the off season. If you missed it, catch up on Off Season Phase One: Rest and Rejuvenation for the importance of taking a break, then read on for Phase Two to learn what optimal off season training could look like.

So you’ve taken some time completely off from training, anywhere from one to three weeks, but now what? You’re feeling mentally and physically recharged, fresh not fatigued, and those troublesome niggles and aches that were simmering in the background for much of the previous race season have finally dissipated. Your body is ready to run, but with races still many months away, you’re not sure what to do next.

With popular running plans structured around a 12 to 16 week training block, three to four months, and the majority of peak races falling somewhere between June and August, that leaves the next three to six months up in the air. It’s time to embrace Phase Two of the off season!

As a coach, I’ve seen athletes take a multitude of different approaches to this “in between” time called off season. Here a three common athlete mentalities:

Athlete 1: “I’m rested and healthy, the body feels fresh and my running mojo is back, so let’s dive into training for my goal race right now. This way I can squeeze in 2 training blocks of 12 to 16 weeks and be even faster and fitter for my race in June!”

Athlete 2: “It’s almost the holidays, Thanksgiving then Christmas then New Years, and the family will be in town and kids home from school soon. Work is ramping up as the year comes to an end, it’s getting colder and darker, and, besides, I’m not racing for over 6 months so I think I’ll extend my rest and recovery then get back to training in January. If I start running regularly again in the new year I’ll still have more than 4 months before race day: plenty of time.”

Athlete 3: “I’m rested and healthy, the body feels fresh and my running mojo is back, but without a race on the calendar for over 6 months, I’m not sure what to do. Life is going to get busier with work and family demands increasing, so I could do with using some of the time I used to spend training here. However, this year I trained hard for months and months, building up my mileage and pace, and definitely don’t want to lose the fitness I’ve gained and have to start from square one again come January. Instead of running 5 days a week at a variety of intensities and durations, I think I’ll stick to 3 short easy runs per week and head to the trails or run longer if I feel like it.”

Do you resonate with any of these athletes?

There’s a good chance you can, because they are all perfectly reasonable approaches to take. However, for reasons I won’t dive deep into today, none of these 3 athlete mindsets are optimal for sustained high performance, running longevity, or having 2024 be your next best running year, regardless of your current age, ability, or running experience. Fortunately, there is another way, so let’s get into it!

Another Approach: The Optimal Off Season

The optimal off season, in my opinion, takes a “minimal effective dose” approach to training. Or rather, doing just enough to maintain your hard earned fitness without incurring mental or physical fatigue. Training is less structured and demanding compared with other times of the year, giving you more flexibility and time for the rest of your life. Simply put, this is the time when social engagements can take precedence over your weekend long run, perhaps you opt for yoga instead of your regular run, or take up pickleball (or other physically demanding activity) without worrying about its impact on your running readiness.

If you read last month’s piece, you might remember that reductions in VO2max, stroke volume, and muscle strength are reported to appear after two weeks of rest. So it’s understandable that runners feel pressure to ramp their training load back up after a break in order to prevent further fitness losses. But “detraining” isn’t quite that scary.

However, you might be surprised by how little training is required to maintain fitness compared to gaining it. If we go back to a 1989 review titled “The Effect of Detraining and Reduced Training on the Physiological Adaptations to Aerobic Exercise Training” they described that these aforementioned adaptations to aerobic training – increased VO2max, stroke volume, and muscle strength – can be retained for several months even when athletes reduce their training frequency and duration by one to two thirds, as long as workout intensity is maintained. Basically you can scale training way down, and maintain all the work you put in this past season. More recent studies, including a 2021 review titled “Maintaining physical performance: The minimal dose of exercise needed to preserve endurance and strength over time”, supported these findings – that training adaptations can be retained while reducing training volumes of 50%, including utilizing cross-training, the caveat again being that intensity must be maintained.

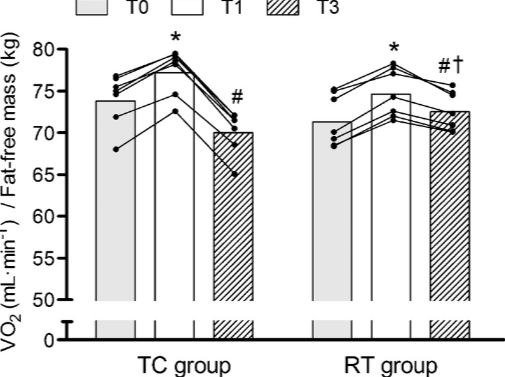

This chart, from a 2010 study titled “Physiological Effects of Tapering and Detraining in World-Class Kayakers”, neatly illustrates how VO2 max can be largely maintained even after nine weeks of very little training compared to complete rest (training cessation). T0 represents athletes’ baseline VO2max, T1 represents athletes’ VO2max following a 43 week training and racing season; T3 represents VO2max following nine weeks of reduced or no training. The bars on the left, labeled TC meaning “training cessation”, show how VO2max rapidly declined to below baseline following total cessation of training. However, as the bars on the right illustrate, improvements in VO2max can be largely retained even when athletes dramatically reduce their training, from an average weekly volume of 7.67 hours to under 2.

Interestingly, during the reduced training period, both volume and intensity was reduced and athletes only engaged in about 25% of their usual training volume, and only at moderate intensities. As mentioned above, maintaining intensity is key to mitigating fitness losses, so had these athletes retained their normal training intensity distribution, which included a substantial amount of high intensity work, and upped volume to around 50% of their usual load, one can assume athletes’ would’ve retained almost all of their training-related VO2max gains. Thus, this chart reassuringly illustrates how a little goes a long way as far as off season training is concerned!

“Less structure” is far from “no structure”, and maintaining fitness and minimizing losses requires careful and considered planning of your off season. In practice, this means focusing on maintaining training intensity rather than trying to hit arbitrary numbers of X hours or Y miles each week.

Applying the science to practice, I recommend athletes maintain around 50% of their normal training volume during Phase Two of their off season. For the athlete used to running 60 minutes five days per week, that would look like dropping down to 30 minutes five days per week and you’ve successfully halved your weekly training hours from 5 to 2.5. And remember, cross training counts too! Have fun mixing it up: perhaps 3 days running, 1 day cycling, and another skiing, or try a dance class with a friend instead, the choice is yours!

As the research has highlighted, maintaining training intensity is essential during the off season. If we use an approximate 80/20 approach to intensity distribution for the aforementioned athlete running five hours per week, approximately one hour is spent working at a high intensity. This distribution should be maintained, or even increased, when total training volume is decreased. To minimize fitness losses, this athlete’s 2.5 weekly off season training hours should still include approximately 30 to 60 minutes of high intensity work.

Here is a very loose template illustrating what I’ve just outlined:

| Day/Season | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun | Total hours (intensity distribution) |

| In season | 40 mins easy run | 60 mins (30 easy, 30 high intensity) | 30 mins easy run 30 mins strength training | Rest day | 60 mins (30 easy, 30 high intensity) | 30 mins easy run 30 mins strength training | 80 mins long run | 5 hours (80% low, 20% high intensity) |

| Off season | Rest day | 60 mins (30 easy, 30 high intensity) | 30 mins strength training | Rest day | 60 mins (45 easy, 15 high intensity) | 30 mins easy bike | 30 mins easy run | 2.5 hours (70% low, 30% high intensity) |

What about the extra time not spent training?

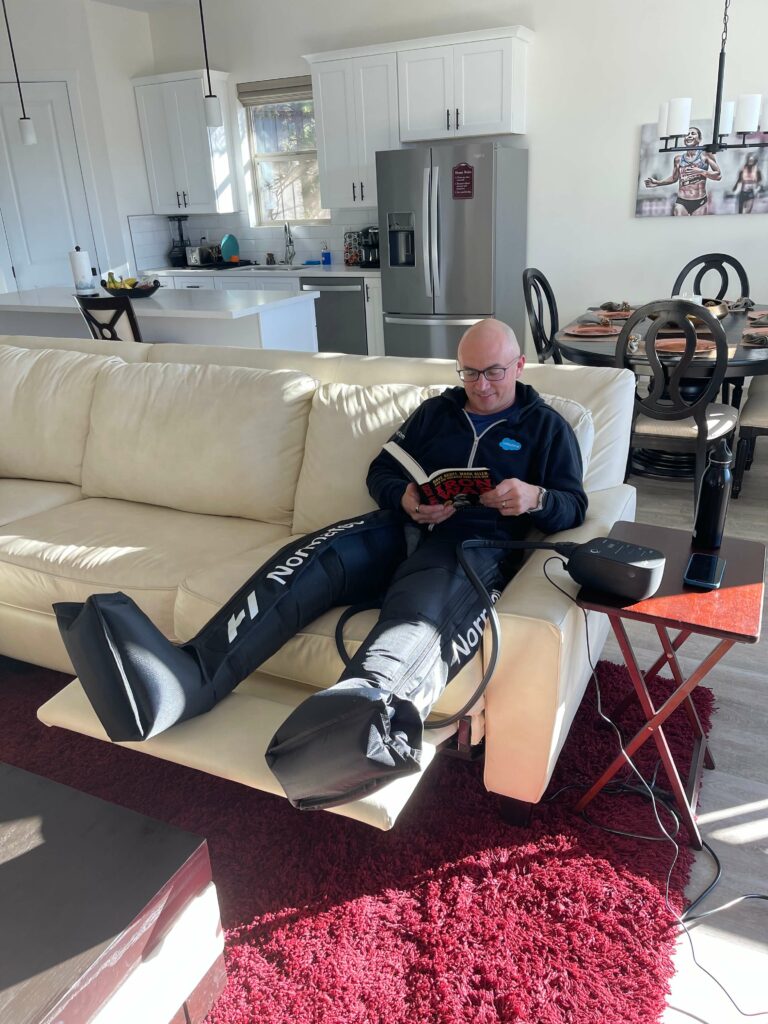

With less time dedicated to training, use some of the “spare” minutes and hours to maintain the rest and recovery-promoting activities you did during Phase One of your off season. Things like sleeping in, home cooking, foam rolling and stretching, warm (or ice cold) baths, relaxing on the couch reading or watching a show. Additionally, I recommend spending more time with friends and family, amending the relationships you might have sacrificed during heavy training, and (yes, I mean it!) overpaying the debt of household chores you owe your partner or housemate from the past six months! (Hint hint: if you plan on asking for favors and allowances for training and racing in 2024, this last point should be a priority!)

Phase two of the off season is also the prime time for building and ingraining habits that will pay dividends in the long run:

- Strength training: Now is the time to start that weekly strength routine you know you should be doing without worrying that additional soreness will negatively impact your running. Start now, maintain the habit, and then when training ramps back up your body will have adapted and worked through any early soreness.

- Fueling: The off season is also the ideal time to experiment with new fueling options. In the case of GI symptoms or negative consequences mid-run, cutting a run short or stopping frequently is no big deal right now. Start dialing in your pre, post, and mid-workout nutrition during the off season, then look forward to beginning your next training block focused on your running not your stomach or energy levels.

- Recovery routines: With extra time not training, commit ten minutes to foam rolling/ body activation/ warming up before every run and ten minutes to basic bodyweight strength/ core exercises/ drills post run. Supporting your run in this way will not only help you feel better during, but recover faster after and lessen your chance of injury. Ingrain this habit now, and soon it will become second nature.

Body changes during the off season

With intentional brevity, let me touch on the topic of body composition changes. It is okay and perfectly normal for your body to change throughout life, including during the off season. With a reduced training load and more time for family functions and social engagements, especially around the holidays, it’s not uncommon to find your clothes fitting differently. Rather than trying to prevent body changes through dietary manipulation and restriction, ignore the number on the scale, change is normal.

Lastly, for athletes seeking weight or body composition changes, the off season is the only time in the training year for actively pursuing these goals. With reduced training loads and additional recovery time, the risks of underfueling-related injuries and illnesses are lower. However, underfueling and subsequent relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) pose harm to all athletes, regardless of body weight and running ability, at any time of year, including during the off season. I caution all readers to consult a registered dietitian before making any dietary changes, and then adopt an additive approach to nutrition rather than a restrictive one. Focus on adding in different colored fruits and vegetables, increasing the diversity of your diet, and fueling enough around your training sessions. Remember, your body shape and size says nothing about your self-worth or moral value, health or athleticism – anyone who runs is a runner, and every runner has a runner’s body.

References

Chen, Y. T., Hsieh, Y. Y., Ho, J. Y., Lin, T. Y., & Lin, J. C. (2022). Two weeks of detraining reduces cardiopulmonary function and muscular fitness in endurance athletes. European Journal of Sport Science, 22(3), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2021.1880647

Neufer P. D. (1989). The effect of detraining and reduced training on the physiological adaptations to aerobic exercise training. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 8(5), 302–320. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-198908050-00004

Mujika, I., & Padilla, S. (2000). Detraining: Loss of training-induced physiological and performance adaptations. Part II: Long term insufficient training stimulus. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 30(3), 145–154. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200030030-00001

Spiering, B. A., Mujika, I., Sharp, M. A., & Foulis, S. A. (2021). Maintaining physical performance: The minimal dose of exercise needed to preserve endurance and strength over time. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 35(5), 1449–1458. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003964

García-Pallarés, J., Sánchez-Medina, L., Pérez, C. E., Izquierdo-Gabarren, M., & Izquierdo, M. (2010). Physiological effects of tapering and detraining in world-class kayakers. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42(6), 1209–1214. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c9228c