Menopause, a time in life whispered about, feared and not talked about enough. A topic that has traditionally been avoided, only talked about in hushed voices, but has been something those who menstruate have been battling alone for years. They’ve been brushed off, often portrayed as emotionally unstable, uncomfortably warm, older women. Menopause marks the transition from reproductive years to non-reproductive years, and while most women will live over 30% of their lives in these post-menopausal years, it has been understudied and misunderstood for decades. Luckily, it is gaining traction, and recently the First Lady even started a new team to tackle menopause research (8). As a coach to many athletes going through menopause, I have witnessed firsthand their frustration navigating the healthcare system and diverse array of confusing symptoms and I hope to be able to one day contribute to this research. In the meantime, I hope to shed some light on the current state of research and what we know today.

One major player in this space is the SWAN study, which will be referenced a lot throughout this article (5). The study has tracked over 3,000 women worldwide for almost 30 years, looking at health biomarkers, lifestyle, and symptoms in relation to the menopause transition (5). This article aims to provide a brief overview of menopause and its symptoms, and some general guidelines around exercise and nutrition during this time. Even though menopause has been gaining momentum, menopause in the context of elite or recreational sport has been studied even less, especially trail and ultrarunning. Because of this we are still left piecing studies and guidelines together and ultimately seeing what works best for each athlete. As always, it is best to consult your medical team when you start to notice symptoms related to menopause to determine what treatment path is most effective for your unique body.

Disclaimer: This article is discussed in terms of biological sex. What I mean by that is that the participants in these studies termed “female” have circulating levels of female sex hormones and were born with an assigned sex of female at birth. This is by no means meant to be exclusionary, however, due to the lack of science on the female sex alone, those who categorize outside of this “neat and tidy” box have not been studied in this space yet. Hopefully, in years to come, the scientific field will also study this in broader scope and can help us provide accurate information around proper fueling techniques to everyone. This article focuses on recommendations around menopause. If you do not menstruate and/or will not go through menopause, that is okay, it is still crucial that you stay in tune with your body and on top of your nutrition. Additionally, some of this knowledge is helpful for aging athletes irrespective of menopausal status.

So what is menopause?

Menopause is part of the normal aging process for females, and marks the cessation of the menstrual cycle, or end of the female reproductive years (10). The average age of menopause in the U.S is roughly 51 years old, however women can go through menopause before the age of 40 or after the age of 55 (10). The menopause transition is typically referred to as perimenopause and is characterized by changes in menstrual cycle frequency (typically more frequent) and length and an increased prevalence of anovulatory cycles (a cycle where bleeding occurs but no ovulation takes place) (5,10). This occurs because the major sex hormone levels (estrogen and progesterone) are changing drastically during this time, and eventually fall to low levels once menopause has been reached (5,10). These changes are not standardized for everyone, there is no “one size fits all”, and this phase can last anywhere from 3-10 years. Cessation of the menstrual cycle for more than 12 months signifies menopause and estrogen and progesterone levels are very low (5). Post menopause is then defined as the time after 12 months without a menstrual cycle (5,10).

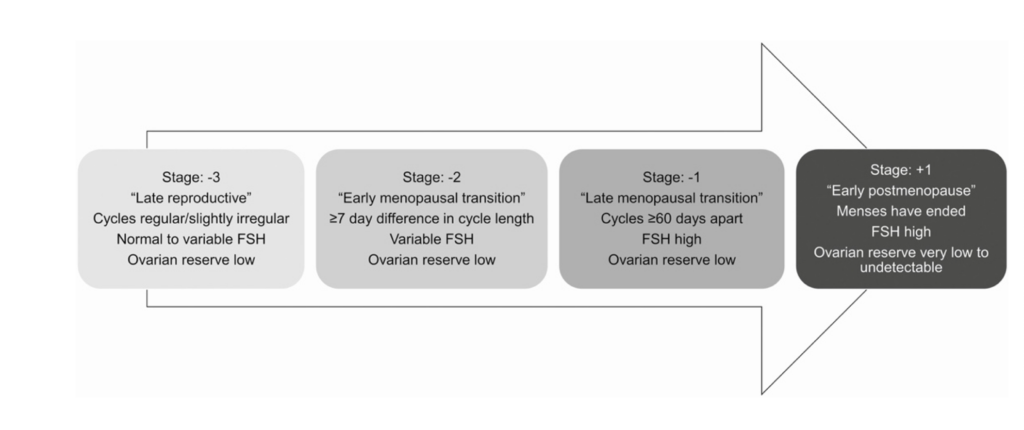

One article I found particularly useful, broke the perimenopausal years into three buckets (13). This is depicted below and describes how the journey may change as everyone gets closer to the cessation of their cycle. For those of you that track your cycle and body temperature every month, you may be able to notice the slight changes earlier on in this journey and be able to anticipate the onset of menopause better.

While menopause is a normal part of aging, the symptoms related to these irregular hormones can be debilitating and typically impact 80% of women. (1,10,13)

Common symptoms:

- Hot flashes

- Mood change (most notably an increase in depression and anxiety)

- Body mass changes (decrease in lean mass, increase in fat mass)

- Decreased metabolism

- Sleep disturbances

- Osteoporosis (lower bone mineral density and higher likelihood of bone fracture)

- Vaginal dryness and/or atrophy (yep, I said it)

- Decreased libido (yep, I also said that)

Let me dive into some of these symptoms.

Hot Flashes

Hot flashes are the most common symptom among menopausal women, with almost 90% of women experiencing them to some degree (10). These can occur during the day or at night, and when they occur at night often lead to sleep disturbances (I see lots of nodding along here). Poor sleep quality is also common during menopause. Although women tend to need less sleep as they age, sleep is still very important, especially for athletes, so making sure your bedroom sets you up with optimal sleep conditions may be a good start to combatting this. If the hot flashes persist frequently and/or get too bad, consult your medical team as there are an array of treatments now that have been shown to help.

Resting Metabolic Rate

Resting metabolic rate (how much energy you burn just to exist) also decreases after menopause, mainly due to the interaction of estrogen in many important pathways. This change in metabolic rate can lead to weight gain and a decrease in muscle in some women, however, women who maintain frequent endurance and resistance training can help mitigate this shift and maintain lean mass (5,10). Due to the lower metabolic rate that accompanies menopause, some women may feel less hungry, which can lead to inadequate caloric intake and increased bone mass loss (5,10). Therefore, it is important to continue to fuel consistently, especially those who exercise, even when you feel less hungry. We will touch more on fueling later.

Changes in Bone and Muscle Mass

Changes in bone mass (also referred to as bone density) is of particular interest to master’s level athletes, because you want to stay injury free, and this is especially true in ultrarunning where the prevalence of bone stress injuries is relatively high. Over the menopause journey, some women can lose up to 5% of bone mass per year after their last menstrual cycle (3). Therefore, making sure to incorporate weight training and high impact activities (running counts) is important in maintaining bone mass. However, anything in excess can be too much of a good thing, and overdoing it could further perpetuate the problem. There is not much research on athletes with RED-S and low energy availability (inadequate energy intake to meet daily and athletic energy demands) who may have impaired metabolic or bone metabolism prior to menopause. For these athletes, it is even more important to pay special attention to energy intake, continue to weight train to maintain bone mass, and speak with your medical team regarding other treatment modalities to keep their bones strong.

All the other symptoms listed may impact women going through menopause, but by no means is this list exhaustive, it’s merely a collection of the most common symptoms. Women of different body sizes and different ethnicities may experience menopause differently, for example, African American women have been shown to potentially have more severe symptoms (5). Since menopause is still being studied, there are bound to be more findings in this area in the future, and if you experiencing other symptoms that you think may be linked to the menopause years, make sure to mention them to your doctor.

Menopause and Exercise

Speaking of symptoms, exercise has been shown to decrease the severity of a lot of symptoms experienced during menopause, specifically hot flashes, sleep disturbances, and insulin sensitivity (7,14).

Overall, exercise is extremely advantageous for mitigating the natural effects of both menopause and aging. With aging comes a decline in performance variables, like VO2 Max (or how efficient your body is at oxygenating blood and moving muscles during exercise) (7,9,14). This is often tied to two key factors, a decrease in lean muscle mass and a decrease in time spent exercise. Which means, with consistent exercise, this decline can be slowed (9). Exercise, particularly high impact sports and weight training, can also help combat osteoporosis by helping to maintain bone mass (1).

When it comes to type of exercise, it is important to do both low/moderate and high intensity activities because each offer different but incredibly important cardiac benefits (11). More research is needed in this area especially regarding ultra-endurance activities, but it is safe to say that staying active and making sure to get out for your run/bike/hike and add in some hard intervals or lifting sessions is in your best interest.

Nutrition Masters

When it comes to nutrition, there are a lot of mixed messages given to women going through menopause. We know that menopause results in a reduced metabolic rate, decreased muscle mass, and increased risk for diabetes (1,10,13). There is a lot at play and it is hard to know what to do. A lot of studies have shown improvements in muscle mass with increased protein ingestion, however most other studies are sparse and inconclusive regarding proper nutrition (1, 3,12,15). With these things in mind, and based off the current, limited research, our in-house Sports Dietician, Dr. Kelly Pritchett PhD has provided us with her current recommendations to athletes going through menopause.

Dr. Pritchett’s Recommendations

- Increase protein intake.

- Aim for 1.8 -2 g/kg per day spacing out throughout the day (0.3- 0.4 g/kg) (12,15).

- Menopausal athletes need more protein than their pre-menopausal counterparts to help maintain muscle mass (1,3).

- Be mindful about your carbohydrate ingestion.

- Aim for 3 to 8 g/kg per day.

- Be strategic fueling pre, during and post exercise with carbohydrates, especially if you notice that carbohydrates outside of exercise do not make you feel as good as they used to.

- Ideally fuel within the 30-minute window post exercise because glucose uptake is not dependent on insulin levels (1,3).

- Avoid long periods of caloric restriction.

- Resist the urge to start any fad or restrictive diets, long periods of starvation can wreak havoc on metabolism and slow it even further.

- Aim for multiple small meals with adequate protein (20-30g) scattered throughout the day.

- Always eat breakfast to increase your metabolism to start off the day and curb cravings later (12).

- Enlist a registered dietician to help with meal planning and supplementation.

- Creatine may be a helpful tool for building lean mass (16).

- Vitamin D and Calcium supplementation may be necessary for bone health if levels obtained from the diet are not adequate (1).

- Iron absorption may be more impaired in menopausal endurance athletes, finding the optimal window to supplement (if you are low) is critical (2)

Hormone therapy

I am not going to cover Hormone Replacement Therapy or other treatments in this article, as they are currently outside the scope of this article. However, I’d be remiss not to mention them at all, as they are highly studied, and I suggest that you work with your physician to determine if hormone therapy is best for you based off your current age, menopausal status, risk for disease, and severity of symptoms (6).

Key Takeaways

Tying all this back to trail and ultrarunning is hard. There have only been a couple of studies on this population with only one study looking at menopausal women specifically, that showed no differences in recovery metrics between pre- and post-menopausal women (4). Other studies have looked at athletes in the age range of menopause but have not collected menopausal status.

What we do know is that endurance activity is good for us, especially for bone and cardiovascular health in women in their menopausal years. We also know that extreme levels of ultra-endurance paired with inadequate fueling can be harmful. Balancing these two truths is tricky, but not impossible. Making sure that you are doing this sport in the healthiest way possible (i.e. fueling properly during and after exercise, hydrating sufficiently, recovering well, strength training, and sleeping) will allow you to reap the positive benefits and less of the negative ones. Thinking of our long-term health is most important, so that we can get to those menopausal years with sufficient bone density to maintain and the metabolism to support it.

Hopefully over the years I will be able to make big updates to articles like this one, showcasing data on endurance athletes going through menopause and strategies for optimizing performance. Until then, keep tracking your cycles and body temperatures and make notes about what works and what doesn’t work for you, so that when menopause hits you feel empowered and in charge of your own body and can present a holistic view of your past menstrual data to your medical team.

Happy running, friends!

References

(1) Agostini, Deborah, et al. “Muscle and Bone Health in Postmenopausal Women: Role of Protein and Vitamin D Supplementation Combined with Exercise Training.” Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 8, 16 Aug. 2018, p. 1103, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6116194/, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10081103.

(2) Alfaro-Magallanes, Víctor, et al. “Menopause Delays the Typical Recovery of Pre-Exercise Hepcidin Levels after High-Intensity Interval Running Exercise in Endurance-Trained Women.” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 12, 17 Dec. 2020, p. 3866, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123866. Accessed 5 Feb. 2021.

(3) Beasley, Jeannette M., et al. “Protein Intake and Incident Frailty in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 58, no. 6, 7 May 2010, pp. 1063–1071, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02866.x.

(4) Copeland, Jennifer, and M.L. Sophia Verzosa. “ENDOCRINE RESPONSE to an ULTRA-MARATHON in PRE- and POST-MENOPAUSAL WOMEN.” Biology of Sport, vol. 31, no. 2, 1 Apr. 2014, pp. 125–131, https://doi.org/10.5604/20831862.1097480. Accessed 22 Mar. 2022.

(5) El Khoudary, Samar R., et al. “The Menopause Transition and Womenʼs Health at Midlife.” Menopause, vol. 26, no. 10, Oct. 2019, pp. 1213–1227, https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0000000000001424.

(6) Faubion, Stephanie . “The 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of the North American Menopause Society.” Menopause (New York, N.Y.), vol. 29, no. 7, 1 July 2022, pp. 767–794, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35797481/, https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000002028.

(7) Graeme Carrick–Ranson, et al. “Effects of Aging and Endurance Exercise Training on Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Cardiac Structure and Function in Healthy Midlife and Older Women.” Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 135, no. 6, 1 Dec. 2023, pp. 1215–1235, https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00798.2022. Accessed 20 Dec. 2023.

(8) Groppe, Maureen. “Why Can’t Women Get Better Care for Menopause or Heart Attacks? Jill Biden Wants Answers.” USA TODAY, 13 Nov. 2023, www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2023/11/13/jill-biden-research-womens-health-issues-menopause/71569223007/. Accessed 19 Dec. 2023.

(9) Hodson, Leanne, et al. “Lower Resting and Total Energy Expenditure in Postmenopausal Compared with Premenopausal Women Matched for Abdominal Obesity.” Journal of Nutritional Science, vol. 3, 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4153012/, https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2013.38. Accessed 20 Aug. 2022.

(10) Minkin, Mary Jane. “Menopause.” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 46, no. 3, Sept. 2019, pp. 501–514, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2019.04.008.

(11) Orri, Julia, et al. “Is Vigorous Exercise Training Superior to Moderate for CVD Risk after Menopause?” Sports Medicine International Open, vol. 1, no. 05, Aug. 2017, pp. E166–E171, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-118094. Accessed 7 Dec. 2020.

(12) Phillips, Stuart M., et al. “Protein “Requirements” beyond the RDA: Implications for Optimizing Health.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, vol. 41, no. 5, May 2016, pp. 565–572, www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/pdf/10.1139/apnm-2015-0550, https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0550.

(13) Santoro, Nanette, et al. “The Menopause Transition: Signs, Symptoms, and Management Options.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 106, no. 1, 23 Oct. 2020, pp. 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa764.

(14) Shabani, Ramin, et al. “The Effect of Eight Weeks Combined Resistance – Endurance Exercise Training on Serum Levels of Serotonin and Sleep Quality in Menopausal Women.” Complementary Medicine Journal, vol. 7, no. 2, 10 Sept. 2017, pp. 1918–1930, cmja.arakmu.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=461&sid=1&slc_lang=en. Accessed 20 Dec. 2023.

(15) Sims, Stacy T, et al. “International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: Nutritional Concerns of the Female Athlete.” JOURNAL of the INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY of SPORTS NUTRITION, vol. 20, no. 1, 24 May 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/15502783.2023.2204066.

(16) Smith-Ryan, Abbie E, et al. “Creatine Supplementation in Women’s Health: A Lifespan Perspective.” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 3, 8 Mar. 2021, p. 877, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030877.